In previous posts we looked at how to use a C.R.U.D. matrix to determine if there were any use cases we

might want to add to the use case diagram to improve test adequacy. We noted that the process of

working through the C.R.U.D. matrix was an important as the matrix itself,

providing “Ah, Ha!” moments with valuable insight into the testing of the

product. When completed the C.R.U.D. matrix was essentially a high level test

case for the entire system, providing expected inputs (read), and outputs

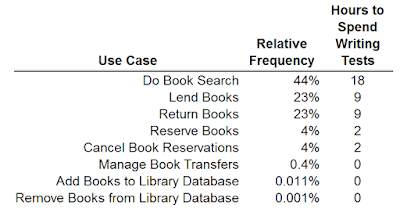

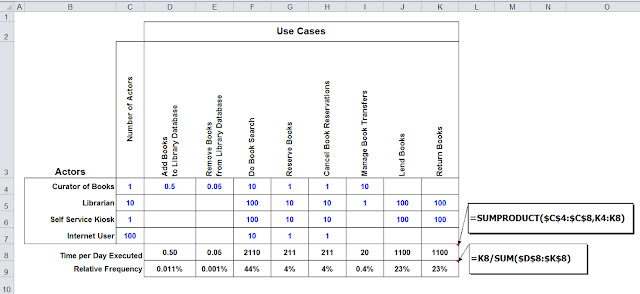

(create, update, delete) for the entire system in a compact, succinct form. We then utilized the use case diagram to develop an operational profile to help with a bit of test planning,

identifying high trafficked use cases in the system, high risk data, and even design of load and stress

tests.

|

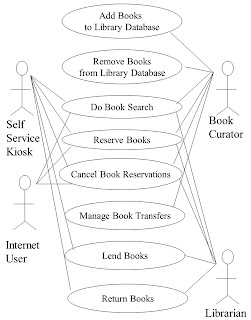

| Library management system use case diagram |

Still working at the use case diagram level – the 30,000-foot view of the system – a

good next step in test design is to ask how the use cases of the diagram

should be tested in concert, i.e. integration testing of the use cases. One obvious way to approach integration testing of use cases is from the perspective of one or more of the actors in the use case diagram. If pressed for time in test design, one might select the view point of a subset of the actors that collectively cover all the use cases in the diagram. For example, referring to the use case diagram in the side bar, one might choose to integration test all use cases from the viewpoints of the Self Service Kiosk and Book Curator actors. In doing so all use cases would be exercised.

An alternate strategy for the integration testing of use cases – the one we’ll focus on

in this post -- is from the perspective of the underlying data. This

approach has the advantage that it can yield tests that cross actor boundaries;

so not only testing use cases in concert, but

actors as

well.

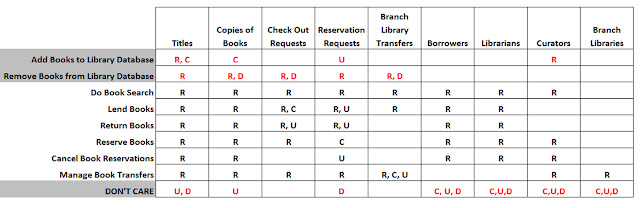

Using the C.R.U.D. matrix below as an example (which we derived in a previous post; this matrix corresponds to the use case diagram above), one begins by selecting a data entity (columns of the C.R.U.D. matrix) from which tests are to be designed. Ideally one would design tests for each data entity (what Martin Pol et.al. prescribes). In a pinch for time, however, one might focus on data entities most critical to the system.

|

| Library management system C.R.U.D. matrix |

For this example let's focus on a “high risk” data entity Check Out Requests (see my book, Chapter 2’s section Risk Exposure and Data on how to identify high risk data entities).

Check Out Requests Example

|

| Use Cases that exercise Check Out Requests |

2. Update data (i.e. a Check Out Request), then read to verify changes

3. Delete data (i.e. a Check Out Request), then try to read to verify the data is really gone

Applying this three step process to these use cases, the following combination of use cases could, for example, be used to data

lifecycle test Check Out Requests:

1)

(Create) Lend a copy or copies of a book, then

a) Do

a search on that book; Confirm checked out status

b) Reserve

a copy for pickup at the library; You shouldn’t get a copy checked out

c) Try

to transfer a checked out book to another library; You should be prevented from

this

2)

(Update) Return a book that was checked out

a) Do

a search and confirm the book status is now checked in

b) Reserve

a book for which all copies were formerly checked out; you should be able to

get the copy that was just checked in

c) Transfer

to another library a copy of a book that formerly checked out, but has just

been checked back in.

3)

(Delete) Delete all copies of a book from the

library (remember, the title remains); doing this removes all check out records

for those copies.

a) Do

a search and confirm no copies are available

b) Confirm

you can’t reserve these deleted books

c) Confirm

you can’t transfer these deleted copies to another library